Automatic Extraction, Classification and Neutralization of Toxic Comments

This is my team’s final project for COSC 89.21 Data Mining and Knowledge with Professor Soroush Vosoughi. Our team consisted of Yakoob Khan, Luca C. L. Lit, Louis Murerwa, and myself. You can find a detailed description of our project here, as below I will describe mostly just my contributions. Anything marked with … was worked on by my wonderful teammates, whereas anything labeled ✅ refers to a contribution of mine.

GitHub

You can find all of our code right here.

Abstract

In this work, we propose a three-part system that automatically extracts controversial online posts, classifies toxic comments into 6 different categories, and neutralizes the offensive language contained in such comments. Our Extractor module leverages the Twitter API to obtain recent posts from Twitter regarding anti-Asian rhetoric related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Our Classifier Module, trained using Jigsaw’s Toxic Comment Classification dataset, is then used to filter posts that are likely to contain toxicity. We explore a variety of classical machine learning models and BERT to identify an accurate hate speech classifier. Finally, our Neutralizer module performs linguistic style transfer by removing the toxic words contained in the filtered posts while still preserving the underlying content. As each of the three modules are independent of each other, our proposed pipeline is generalizable to automatically extract data from other sources (e.g Reddit), classify and neutralize toxicity using other techniques by replacing the appropriate sub-module.

Introduction

The rise of social media platforms has transformed the way individuals communicate today. While offering numerous benefits, the anonymous nature of such mediums empowers bad actors to promulgate toxic comments that go against the principles of civilized discourse. Being able to automatically detect offensive posts is crucial to ensuring that social media remains healthy and inclusive for all. To assist in this effort, our work proposes a three-part system that automatically extracts comments from an online platform, accurately classifies the posts to filter toxic comments, and finally neutralizes the offensive language. Given the nature of this work, we caution readers that the examples used in this work contain offensive language and reader discretion is advised.

Related Work

There has been extensive work in the study of hate speech detection in the literature. Numerous offensive language datasets (Wulczyn et. al., 2017) with various toxic taxonomies have been created to assist the training of robust computational models for detecting offensive language. Competitions on hate speech detection (Zampieri et. al, 2020), such as the Kaggle Toxic Comments Classification Challenge on which this work is based, have further attraction to this topic. While a lot of attention has been placed on the classification of toxic comments, neutralizing offensive language through text style transfer (Hu et. al, 2020) have been relatively under-studied.

Data Scraping

…

In addition, we also leveraged datasets from Kaggle’s Toxic Comment Classification Challenge as training and testing data for our toxic comment detection models, described in sections 5 and 6. The data is in the form of comments, all of which are sourced from Wikipedia talk page comments. The classifications of toxicity are labeled by human raters detecting instances of derogatory language. In total, a total of 159,571 comments constituted the training dataset, and 153,164 comments for the testing set.

Exploratory Data Analysis

…

Classical Machine Learning Models ✅

Our first approach to classify our dataset was to employ the use of 3 classical machine learning classifiers: Naive Bayes, Logistic Regression and Random Forest. By default, these classifiers actively support classification for no more than two classes so they can only assign a single label to a piece of text. For example, a sample text like “louis went home” can be assigned one binary a$[0,1]$$ label like “toxic.” To achieve Multi-label classification, we employed the use of the “One vs Rest Classifier” which is a heuristic method for using binary classification algorithms on multi-label classification problems. To enhance the performance of the ML models, we employed data pre-processing techniques such as the conversion of popular short phrases like “what’s” and “cuse” to “what is” and “excuse” which is their un-shortened form. We created two similar sets of training sets, one which was lowered and the other one which is unlowered and we also removed stopwords to save up valuable processing time and focus on important word keys. Lastly we employed the use of the CountVectorizer and the TF-IDF Vectorizer to fine tune our predictions.

Deep Learning-based Models ✅

Alongside our aforementioned classical machine learning-based models, we also try an end-to-end, feature learning-based approach that bypasses having to tediously construct a feature set by hand.

Having seen LSTM-based approaches being used in past works to model, say, sentences for the task of complex word identification (Hartmann and dos Santos, 2018; De Hertog and Tack, 2018), we were tempted to implement such an approach. An issue with an LSTM is its ability to read tokens of an input sentence sequentially in a single direction. This inspired us to instead try a Transformer-based approach (Vaswani et al., 2017), architectures that process sentences as a whole (not word-by-word) through the use of attention mechanisms. Attention weights can be interpreted as learned relationships between words. BERT (Devlin et al., 2018) is one such model used for a variety of natural language understanding tasks. We harnessed HuggingFace’s Transformers library to fine-tune a pre-trained BERT base model.

Results ✅

Analysis ✅

In the following sections, we comment on the classification performance of the various models we experimented with for toxic comment detection.

Classical Machine Learning Models

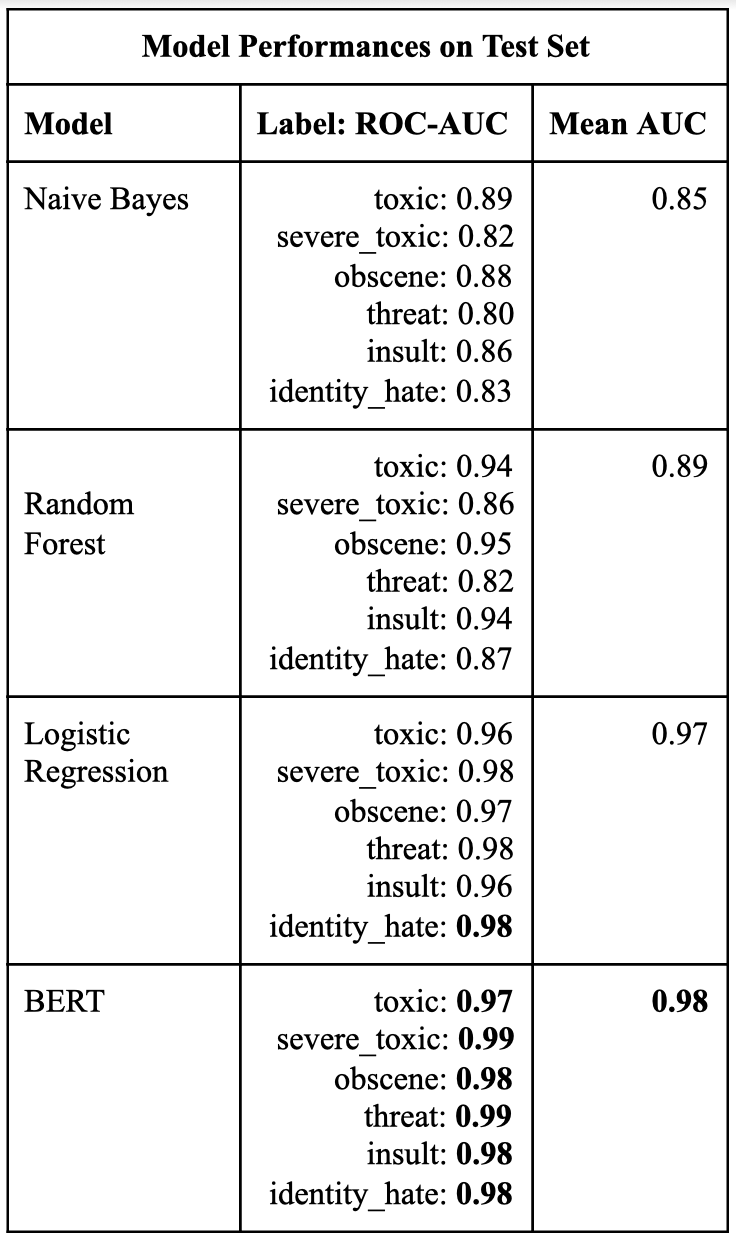

The first step toward discovering the best machine learning model for our toxic tweet dataset was to train all the three potential classic classifiers with multiple features and text pre-processing that would potentially maximize the model performances. We used a combination of 3 classifiers, 2 text pre-processing variations (lowered and unlowered) and 2 Vectorizers (CountVectorizer and TfidfVectorizer). These combinations allowed us to create a total of 12 classifier-feature-vectorizer models from which we picked our best model. The performances of our classic machine learning models varied greatly depending on the tuning mentioned above but the three best models for each classifier had an average AUC of 0.85 for Naive Bayes, 0.9 for Random Forest and 0.97 for Logistic Regression. The Logistic Regression classifier in combination with the TfidfVectorizer and the lowered text exceeded our expectations as it rivaled the performance of our best deep learning model, BERT, which had a mean AUC of 0.98.

Some of the limitations faced in using classical learning models for multi-label classification was that all of these models tend to underperform when there are multiple labels or non-linear boundaries. They take a lot of processing time and when coupled with multiple features they don’t scale very well. Despite these limitations, our Logistic Regression model surpassed expectations and we were impressed by its ability to rival BERT.

BERT

We seek to understand the potential token relationships learned by the BERT model that may be predictive of a given comment’s toxicity. We study the attention maps produced for each sample in our dev set. For each dev set sample, we extract 144 attention maps, ie. one from each of BERT’s attention heads. Each attention map is a 2D matrix, where an arbitrary cell \((i, j)\) contains how much (a ratio from 0-1) the \(i\)th token of a given comment attends to the \(j\)th token of the comment (where \(0 \leq i, j < n+2\)). Note: each comment comprises a list of \(n\) tokens, but BERT prepends the [CLS] token to the start of the list for classification purposes, and [SEP] token to the end of the list as a sort of no-op, yielding a total of \(n+2\) tokens.

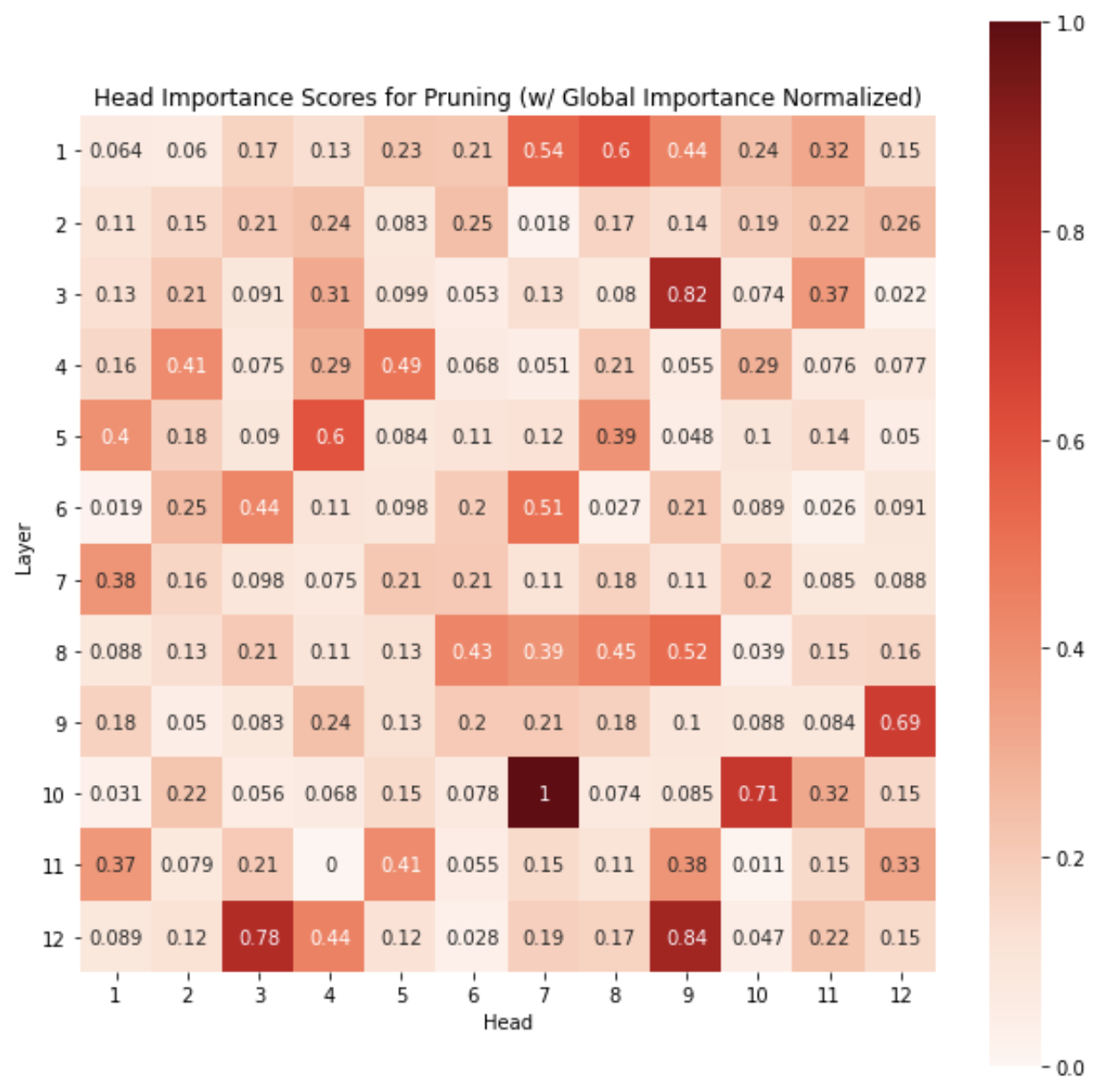

To get a sense of which attention heads are most ‘important’ for our multi-label classification task, we apply an approach devised by Michel et al. 2019 that quantifies the importance of each attention head as the sensitivity of the model to the attention head’s being masked. This requires a single backward and forward pass of the model over the dev set, and accumulation of gradients of the loss function. This yields head importance scores as shown below, revealing that the majority of attention heads can even be pruned:

Figure 1: Attention Head Importance Scores

Figure 1: Attention Head Importance Scores

Due to time constraints, we limit our examination to just one of interesting heads: \((10, 7)\). It appears to have the (global) maximum importance score across all attention heads. We may benefit from a closer look at the relationships learned by this particular head.

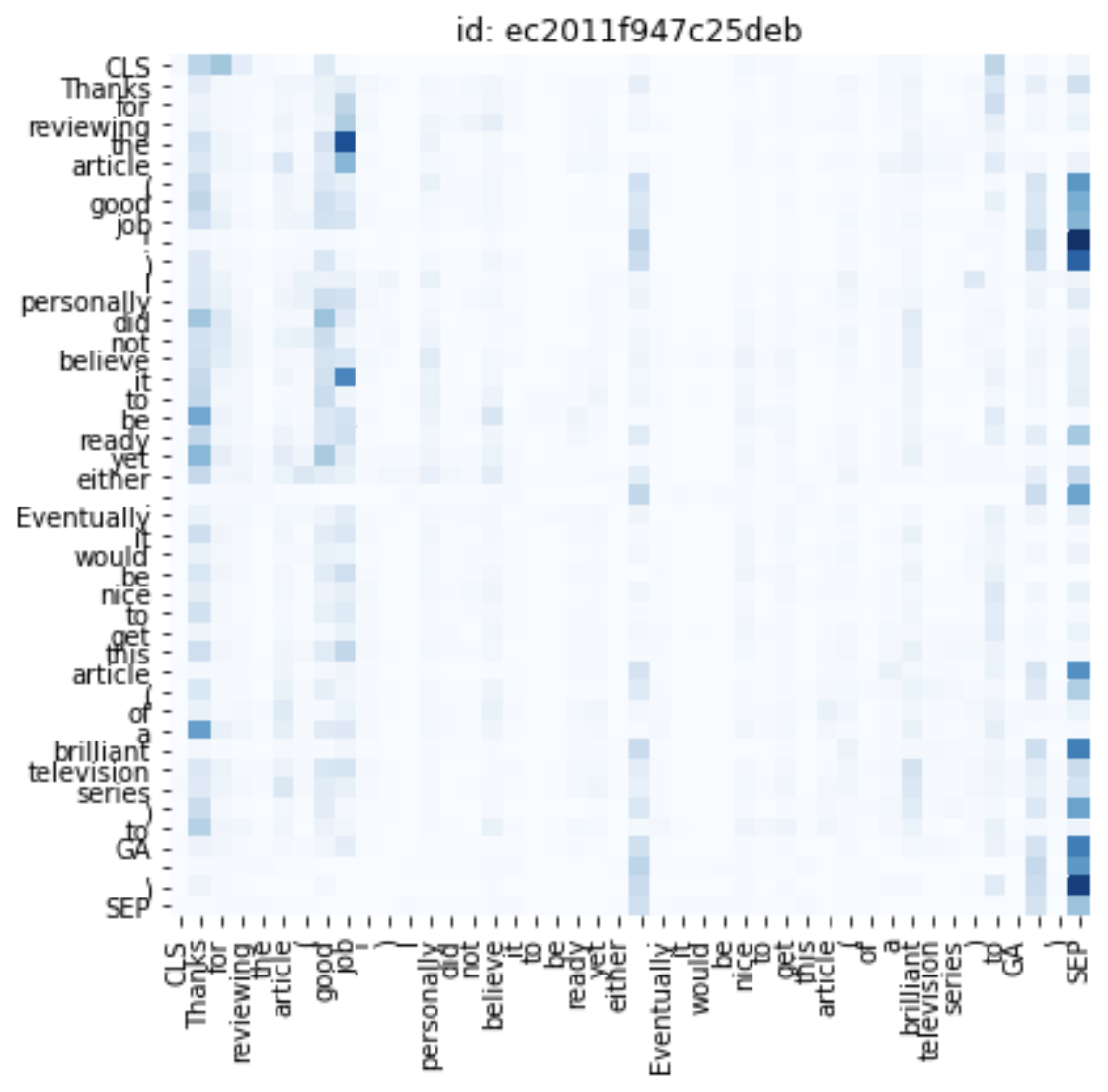

Below we show attention maps at head \((10, 7)\) for two particular dev set examples, where it appears that attention is generally given to tokens that are most indicative of a comment’s tone. This occasionally yields vertical stripe patterns over tokens that are critical to our perception of the given comment:

Figure 2: Attention Map at Head \((10, 7)\) for Random Test Set Sample 1

Figure 2: Attention Map at Head \((10, 7)\) for Random Test Set Sample 1

In the mapping shown above, notice how tokens/phrases given attention to include ‘Thanks’, ‘good job’, ‘brilliant’, as well as punctuation. It seems as though the positive praise given by the comment’s author to the intended reader is being identified by the attention head. The apparent attention given to punctuation is harder to interpret as BERT may be more finicky with punctuation.

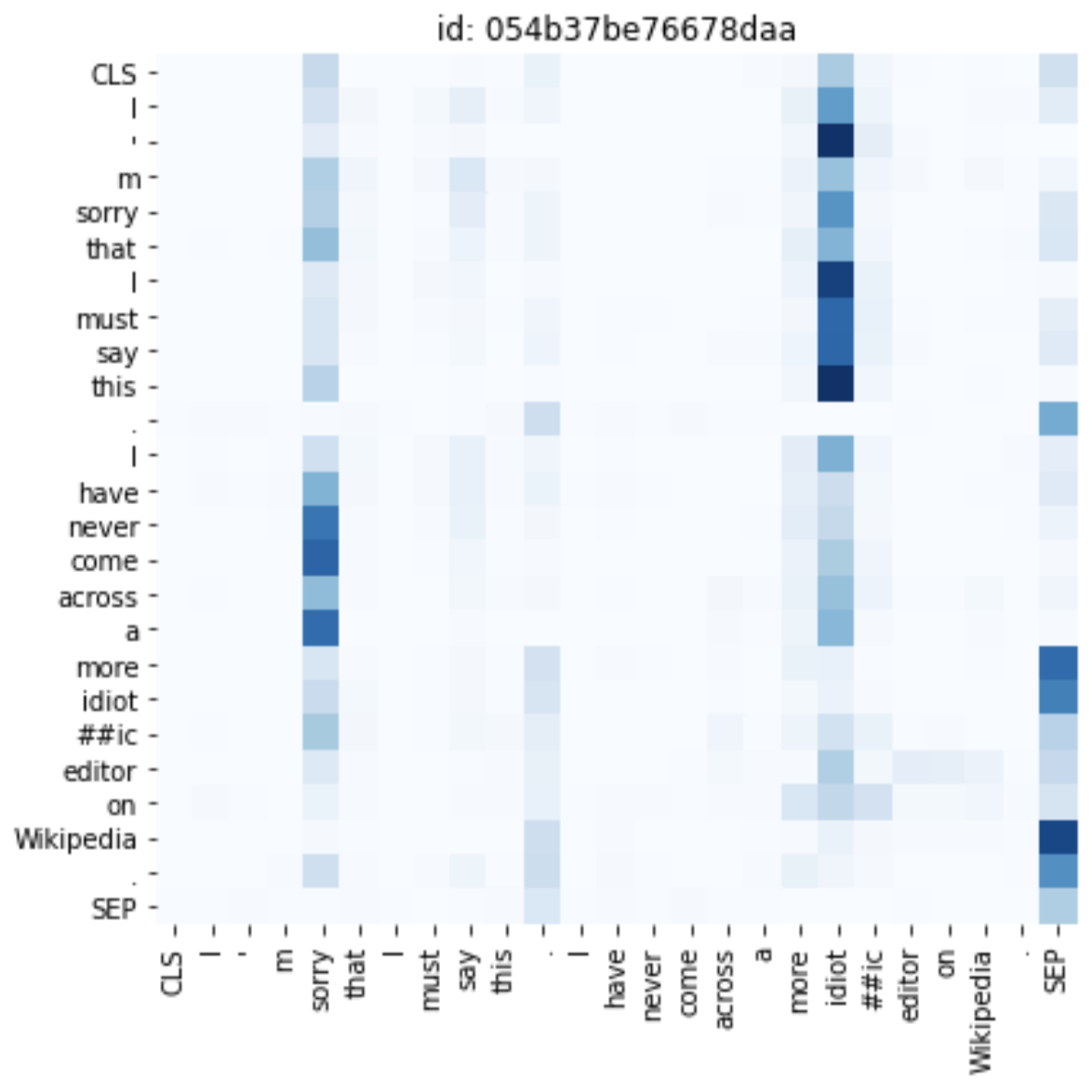

In contrast, the mapping shown below is for a comment exhibiting a relatively more complex tone to decipher; tokens that are heavily attended to include ‘sorry,’ potentially capturing the author’s initial apologetic tone, as well as ‘idiot’ (ie. the root of the word ‘idiotic’), pertaining to the author’s eventual harsh criticism of a supposed editor. This makes some intuitive sense, as both tokens play pivotal roles in embodying how the author’s voice comes across; perhaps comments that sound more aggressive are more often toxic. We believe that such attention maps produced by the BERT model indicate the immense promise of deep learning-based approaches in conducting semantic analysis on text, even with very minimal fine-tuning.

Attention Map at Head \((10, 7)\) for Random Test Set Sample 2

Attention Map at Head \((10, 7)\) for Random Test Set Sample 2

Text Style Transfer

…

Conclusion and Future Work

In this work, we used the Extractor module to scrape recent tweets related to the rise of anti-Asian sentiment related to the COVID-19 pandemic. We showed how the Classifier module can be trained using the Toxic Comments Classification Challenge dataset to create a robust, fine-grained toxic comments detector. Finally, we demonstrated how the Neutralizer module uses a simple rule-based word substitution approach that can be surprisingly effective in text style transfer to disentangle content and style. The independence of each module enables our system to be generalizable across data sources and computational models.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Soroush Vosoughi and the Teaching Assistant team for the wonderful course on Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery (Winter 2021).

References

Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. 2018. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. CoRR, abs/1810.04805.

Nathan Hartmann and Leandro Borges dos Santos. 2018. NILC at CWI 2018: Exploring feature engineering and feature learning. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth Workshop on Innovative Use of NLP for Building Educational Applications, pages 335–340, New Orleans, Louisiana. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Dirk De Hertog and Anaïs Tack. 2018. Deep learning architecture for complex word identification. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth Workshop on Innovative Use of NLP for Building Educational Applications, pages 328–334, New Orleans, Louisiana. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Zhiqiang Hu, Roy Ka-Wei Lee, and Charu C. Aggarwal. 2020. Text Style Transfer: A Review and Experimental Evaluation. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2010.12742.pdf

Paul Michel and Omer Levy and Graham Neubig, . “Are Sixteen Heads Really Better than One?”. CoRR, abs/1905.10650. (2019).

Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N.Gomez, Lukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. 2017. Attention is all you need. CoRR, abs/1706.03762.

Ellery Wulczyn, Nithum Thain, and Lucas Dixon. 2017. Ex machina: Personal attacks seen at scale. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web, WWW ’17, page 1391–1399, Republic and Canton of Geneva, CHE. International World Wide Web Conferences Steering Committee.

Marcos Zampieri, Preslav Nakov, Sara Rosenthal, Pepa Atanasova, Georgi Karadzhov, Hamdy Mubarak, Leon Derczynski, Zeses Pitenis, and Cagri Coltekin. 2020. SemEval-2020 task 12: Multilingual offensive language identification in social media (OffensEval 2020). In Proceedings of the Fourteenth Workshop on Semantic Evaluation, pages 1425– 1447, Barcelona (online). International Committee for Computational Linguistics.